Yes, you heard it here first! I have officially released my 2020 Tapteil Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon. But if you haven’t got the jab, you aren’t getting the cab.

|

| 2020 Tapteil Vineyard Cab Sauv |

2020 was the first, but unfortunately not the last, pandemic vintage. When I wrote my blog post on Pandemic Winemaking last August, harvest was impending even as the delta variant of the coronavirus raged on.

Since then, the rate of virus mutation has outpaced the speed to inject vaccines into people’s arms. There is a lot misinformation about natural immunity being more effective than vaccination. Such sentiments continue despite the rising COVID death rate among the unvaccinated, the general consensus of the medical community, and a robust history of inoculation that dates back to the 1790s.

Inoculation, as a phenomenon, is not just a human experience. In fact, virtually all commercially made and many homemade wine are inoculated and oftentimes twice if it is a red.

Inoculation in the Wine World

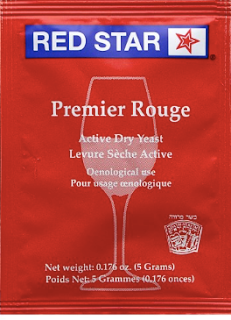

Yeast is what turns grape juice into wine. In winemaking, crushed or pressed grapes (known as must) are typically inoculated with a wine yeast called Saccharomyces cerevisiae or S. cerevisiae to kick start the alcoholic fermentation.

In the last few years, the “natural” wine fad has grown in popularity. The perception is that wine made with wild yeasts in the air is superior to the one made by inoculating cultured yeasts. After all, according to the argument, spontaneous fermentation of grapes was how wine was discovered in the “old days.”

|

| Commercial S. cerevisiae |

I remembered taking a Wine History class where we had to taste a series of wines made in the “old ways.” They didn’t taste very good. In fact, Ancient Greeks mixed their wine with sea water in the ratio of four parts sea water to one part wine. In a similar fashion, the Romans diluted their wine for libation. That makes you wonder how the wine must taste back then.

If Inoculated Fermentation is Like Vaccination

S. cerevisiae is the commercially available yeast used in winemaking. The most conservative approach after harvest is to add sulfite to the must to kill off any wild yeasts and bacteria. After a couple of days when the sulfite is no longer active, the winemaker will then inoculate the must with S. cerevisiae. It is the most reliable yeast specie to complete alcoholic fermentation, which is important on two counts.

|

| Acclimating yeast starter to must |

First, virtually no sugar is left when alcoholic fermentation is complete. Sugar attracts microbial activities, which cause wine to turn into vinegar. The lack of sugar limits the potential for spoilage. Second, alcohol inhibits bacterial growth. Complete fermentation usually results in 12-14% alcohol content, which provides additional protection to the wine.

Although believed to have originated from grape skin, naturally occurring S. cerevisiae make up a minuscule fraction (0.00005% to 0.1%) of the fungal community in ripe grapes. Relying on ambient S. cerevisiae to kick off fermentation is unpredictable. So what about the other naturally occurring yeasts in the vineyard?

Then Spontaneous Fermentation is Like Natural Immunity

To count on naturally occurring yeasts in the vineyard for fermentation means that you are at the mercy of having a critical mass of the right yeast species to kick off a spontaneous fermentation. In the best case scenario, spontaneous fermentation takes off. Now you hope that whatever the wild yeast species involved in the fermentation do not give out undesirable aromas or off-flavors to the wine.

|

| Ripening grapes |

By far the biggest challenge with using naturally occurring yeasts is stuck fermentation. Most wild yeast species do not tolerate more than 6% alcohol content. This means that the yeasts die off before all the sugar is converted to alcohol. The end result is a high sugar and low alcohol wine that becomes a magnet for microbial activities and is prone to vinegarizing.

Theoretically, it is possible to start spontaneous fermentation with wild yeasts and then inoculate with S. cerevisiae to ensure the fermentation is complete to dryness (or no sugar). This requires a skilled winemaker and a well-established vineyard fungal community. In the best of both worlds, the wine gets its unique character from the wild yeasts and the longevity from the inoculated yeasts. But if you have to pick only one fermentation approach, inoculated fermentation is definitely the way to go.

|

| Cabernet Sauvignon grapes from Tapteil |

My Verdict: For me, relying solely on spontaneous fermentation to make wine is like counting only on natural immunity (or immunity by infection) for protection during the pandemic. It may work, but it sure is chancy. I’d rather take the sure bet of an inoculated fermentation to make a good quality wine and vaccines to be my best defense during the pandemic.

My Tasting Notes: No Jab? No Cab has a fruit forward bouquet of tart cherry, fig, plum jam, and brined olive. On the palate, it is jammy with concentrated tart cherry and a slight cocoa aftertaste. The wine is full-bodied with high acidity and a tiny explosion of very fine tannins. The finish lingers and is tart at the back of the mouth.